Michael Crook, son of international communist fighters and pioneers of English education in China, David and Isabel Crook, holds dual citizenship in Britain and Canada. Born in Beijing in 1951, he graduated from the University of London in 1978 and founded the Western Academy of Beijing in 1994 to provide high-quality education for the children of expatriates working in Beijing.

The Western Academy of Beijing is located in the northeastern part of Beijing, where Crook chose to meet with Global People journalists. At 8 a.m., he left his home in the west of the city, drove across half of Beijing. By 9 a.m., he arrived in a hurry, greeting the reporters warmly.

At 73 years old, Crook is hale and hearty,still brisk in his steps. On the day of the interview, he wore a pink checkered shirt under a navy wool cardigan, giving off a distinctly British charm. But the moment he spoke, his fluent Beijing dialect made the conversation feel like a cross-talk performance, filling the room with laughter.

Since birth, Michael Crook’s name has been intertwined with Chinese education. His parents, from Britain and Canada respectively, devoted their lives to China's educational development. In the 1950s, Crook grew up in the faculty housing of Beijing Foreign Studies University, attending some of Beijing’s best schools. Following China’s reform and opening-up, he established the Western Academy of Beijing to address the educational needs of expatriate families in Beijing. It’s fair to say Crook is one of the foreigners who best understands Chinese education.

When sharing his story, Crook always circles back to education. From his transformation from a struggling student to a successful one, to his experiences working as a laborer in Britain, and then founding the Western Academy of Beijing, his narrative is deeply rooted in this field. He also reflects on his parents’ dedication to Chinese education in their later years and marvels at the trans-formative changes he has witnessed in the Chinese educational system since his retirement.

In November 2024, Michael Crook was interviewed by Global People reporters in Beijing. (Photo by Hou Xinying / Global People)

A slower student turned the table

Crook’s story begins long before he was born.

In 1912 and 1913, his grandparents, Homer G. Brown and Muriel J. Hockey, traveled from Canada to Chengdu, China, where they met and married. “My grandfather served as the head of the Education Department at West China Union University, while my grandmother established a Montessori kindergarten and Dewey Primary School. Later, even my great-grandmother came to China to teach at a Canadian school in Chengdu. They devoted their lives to education for decades.”

In 1915, Crook’s mother Isabel was born in Chengdu. She returned to Canada for university and came back to China in 1939. In 1942, she married David Crook, a British communist teaching at the former Nanjing University. In 1948, the Crooks moved to a village near Shijiazhuang called Nanhaishan, where they helped establish the Central Foreign Affairs School, which later became the Beijing Foreign Studies University (BFSU). “During those years, my parents trained many foreign language talents for China. Their students included judges at international courts, diplomats at embassies, and corporate professionals, something they were always proud of.”

Despite being surrounded by educators in the BFSU faculty compound, young Crook’s early years were marked by poor academic performance. “I was mischievous, inattentive, and skipped classes, always at the bottom of the class. But my parents never criticized me for poor grades. Somehow, in fifth grade, my academic performance began to improve.”

Looking back, Crook recognizes the subtle influences shaping him. For instance, he once quoted Chairman Mao’s sayings in an essay, earning his teacher’s praise. “My father, a communist, loved to lecture me on Marxism, and our home had copies of Quotations from Chairman Mao. I knew it by heart.”

Crook attended BFSU’s kindergarten and elementary school before transferring to Chongwen Elementary School in fourth grade, where he began boarding. “I’ve always believed there’s no such thing as a ‘good’ or ‘bad’ school. Some kids dislike boarding school and cry about it, but I adapted well. Before entering high school in Beijing, I even spent a year studying in Britain. My mother later recalled seeing me off at the airport; she waved enthusiastically, but I didn’t look back once and went straight onto the plane. Isn’t that the independence today’s parents hope for their children?”

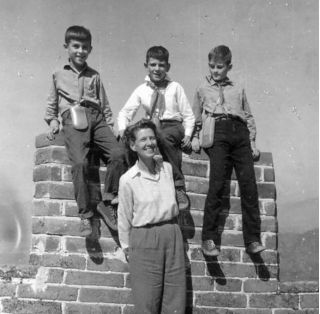

In the 1960s, Isabel (front) took her children to climb the Great Wall. Michael Crook is in the middle of the back row.

After attending The Affiliated High School of Peking University for a while, Crook voluntarily joined the Beijing Guanghua Timber Factory and later worked at the Haidian Agricultural Machinery Maintenance Factory for several months. “This was a fascinating experience,” Crook said. “When I turned six, my father gave me a saw as a birthday gift. Can you imagine a six-year-old getting a saw? Thanks to my parents’ intentional guidance, I developed a love for working with my hands early on, and I can still fix cars today. Sometimes, I can tell what’s wrong with an engine just by listening to its sound.”

In 1973, Crook went to the United Kingdom to attend university, majoring in physics. Struggling financially, he first worked in a London factory to save for tuition. After starting school, he took on two part-time jobs—teaching Chinese at a night school and working as a lifeguard at a swimming pool.

It was at the night school where Crook met a British-born Chinese woman. They fell in love and eventually married. “A British man born in Beijing marrying a Chinese woman born in London—when we registered for marriage, the registrar looked at us and said, ‘Wait, are your birthplaces reversed?’”

Establishing a School for Foreign Kids in China

Crook graduated from university in 1978 and returned to China with his wife. At the time, the University of Science and Technology of China had just established its Graduate School—the first graduate school in China, where Crook landed a job teaching physics.

“That was the year China began its Reform and Opening-Up policy. Before that, studying abroad was rare in the 1960s and ’70s. But by 1978, it was like a door had suddenly opened. At the graduate school where I taught, 80% of the students aspired to study overseas. Eventually, the school administration told me, ‘We don’t really need a physics teacher—how about teaching English instead?’”

This marked Crook’s transition to teaching English. Not long after, he received an offer to teach at Wesleyan University in the United States. From 1981, he taught Chinese language and culture there. In 1988, he returned to China and joined the Canadian International Development Agency. During those years, he traveled across China on various exchange projects, which inspired him to “do something on his own.” The Reform and Opening-Up provided a vast stage for his ambitions.

“In 1993, my American friend Sabina Brady had her child enrolled in an international school in Beijing, but she wasn’t satisfied with the school. She approached me and asked if I would be interested in co-founding a new international school. Knowing my background growing up in an academic environment and my understanding of Chinese education, she thought I’d be the perfect partner.” They agreed immediately and decided to establish an international school rooted in China.

“Since the Reform and Opening-Up, China has attracted many foreign professionals. The movement of talent created a demand for education tailored to expatriate children. In 1994, we founded the Western Academy of Beijing, with the primary mission of providing expatriate children with a suitable educational environment,” Crook explained.

Crook believes the uniqueness of the Western Academy of Beijing lies in its fusion of international and local elements. “‘Western’ refers to the Western educational model, while ‘Beijing’ refers to being located in Beijing. We strive to bridge the gap between the two, allowing foreign students to experience the richness of Chinese culture. Whether they stay for a month or ten years, we hope they leave with friendships with China and its people.”

At the Western Academy of Beijing, every grade includes classes on Chinese language and culture, which also seamlessly integrated into other subjects. “In PE, students practice Tai Chi; in music, they learn the erhu; during the Mid-Autumn Festival, they make mooncakes; for Lunar New Year, they attend temple fairs.” From the start, the school established a China Studies Department, with Crook as its first director. Even in retirement, he continues to serve as an advisor for the department.

A statue of Confucius at the Western Academy of Beijing.

Some shared values between East and West have also become key elements of the campus. Crook hopes that “WAB is diverse, enriched, and a place where differences are respected. At the heart of the campus is a small park called Peace Park. It’s a symbol of harmony. The children here come from different countries, speak different languages, and follow different beliefs, but none of them would ever prefer war over peace.”

To date, the Western Academy of Beijing has been running for 30 years, employing nearly 400 staff and enrolling over 1,500 students from around 60 countries. “Decades ago, foreign professionals would always weigh their children’s educational prospects before coming to China. Some chose to leave their children behind, while others gave up opportunities in China due to a lack of suitable schools. Nowadays, thanks to schools like WAB, this has become less of an issue. As far as I know, more and more foreign families no longer hesitate to come because of education. China’s deepening reform and opening up, with social stability and economic growth soaring, have created increasingly favorable conditions for both Chinese and foreign children,” Crook said.

Wherever I Go, I Visit Local Schools

Crook grew up hearing stories from his parents about the development of Chinese education. The most striking transformation he observed is its increasing accessibility. “In 1949, the average educational level barely reached first grade. In the revolutionary base areas where my parents worked, very few children could attend school. But by 1958, when my parents revisited those villages, there were primary schools, and every school-aged child was enrolled. In the 1980s, the Compulsory Education Law was implemented, ensuring nine years of schooling for about 90% of children. Later, education extended beyond nine years, with most teens completing high school. Today, higher education is becoming widely accessible too.”

Since retiring in 2016 at age 65, Crook remains active, often joining WAB-organized study trips across China. Wherever he goes, he makes a point of visiting local schools.

Last year, Crook visited Nyingchi in Xizang. In a small village, he struck up a lively conversation with a local family. “Does the village have a school?” he asked. “No,” they replied. “How do the children get an education?” “There’s a road now, built by the government, so our children can take a car to the school in the neighboring village—it’s just a 20-minute drive away.” “Is there a school bus?” Crook asked. The man pointed to a white car parked in his yard and said proudly, “We have our own car. Everyone in the village is rich now—we don’t need a school bus; we drive our kids ourselves.”

In a local primary school, Crook attended a Tibetan language class, sitting quietly in the last row for the entire lesson. “The class lasted about forty to fifty minutes. The teacher didn’t speak a word of Mandarin, nor did a single Han Chinese character appear on the blackboard. I flipped through their textbooks—apart from the final page listing the publisher’s information in Han Chinese, everything was in Tibetan language. After class, I asked the kids, ‘Which is better, Tibetan or Mandarin?’ They all replied in unison, ‘Both are good.’ At that moment, I felt so warm. I realized that just like me, who who grew up in China and became fluent in two languages and familiar with two cultures. It is a blessing.”

In May 2023, Michael Crook visited the Second Primary School of Nyingchi City. The photo shows Crook (front row, second from the right) dancing with Tibetan locals.

This experience reminded Crook of Xizang’s educational situation many years ago: “According to China’s official education yearbook, in the 1980s, Xizang had the lowest educational attainment in China. Today, the changes there are astonishing.”

Crook told Global People: “China’s rural education was a priority for my mother in her later years. She always believed that the focus should be on 'raising the bottom,' not just ‘selecting the top.’ In recent years, China has achieved a globally recognized poverty-alleviation effort, which is remarkable. And anti-poverty in China include not just material improvements but also educational advancements, especially for the most remote and disadvantaged areas.”

(Intern Zhang Linjia contributed to this story.)

Editor:Mao Yufei and Dong Shuo

Editor:Mao Yufei and Dong Shuo